30 Years of Change in Single-Parent Household Finances

American family finances have weathered the fallout of the dot-com bubble, the Great Recession and a pandemic over the last 30 years. Despite these challenges and more, single-parent households as a whole have actually seen broad financial improvements during this time.

Some households are better insulated to emerge unscathed (and even improved) from economic turmoil. On the other hand, families with one earner and multiple mouths to feed are at a disadvantage compared with those with multiple incomes when there is a job loss, high inflation, unexpected medical expenses or trouble in financial markets, for example. Measuring the financial health of a single-income household against one with two incomes would uncover few surprises. However, examining how the financial well-being of single-parent households has changed, and how it’s changed relative to others over time, tells a story of certain improvements and remaining opportunities for growth.

I am the product of a single-parent household. From the time I was 3 years old in the early 1980s, my mom raised my older brothers and me solo. Later, as an adult, I was the head of a single-parent household, raising my daughter who was born in 2000. Much has changed during that time, both in how I experienced the world through finances personally and within the broader economy. Charting the household finances of single-parent households across decades underscores these changes. Income, net worth and homeownership rates among single-parent households have improved dramatically, but these households still lack insulation from financial shocks, according to data from the Federal Reserve.

Family finances through the decades

The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances is released every three years and is a trove of household financial data. I examined 30 years of the data, from 1992 to the recently released 2022 report, to see how my lived experiences aligned with the national picture and how the financial conditions of households like mine have changed.

Roughly 30 years ago, in 1992, I was 14 years old, living with my mother and one older brother, while my eldest brother was in college. During childhood, my mom received child support, but we still qualified for the free lunch program at school, a common proxy for household poverty. She had the good fortune of always having a steady job and put herself through college while raising us.

My experience as a parent — beginning in 2000 — was different in that I didn’t receive support payments from another parent but did qualify for broader public assistance. When my daughter was an infant, I received EBT benefits or “food stamps,” public housing and Aid to Dependent Children, commonly referred to as “welfare.” I, too, put myself through college and held down a job from the time she was born. Despite beginning my journey as a single mother at a deficit from where my mother began hers — quite a bit younger and with only one source of income — I was able to climb more quickly, perhaps because I only had one additional mouth to feed or because government and social supports of the era made it easier to do so.

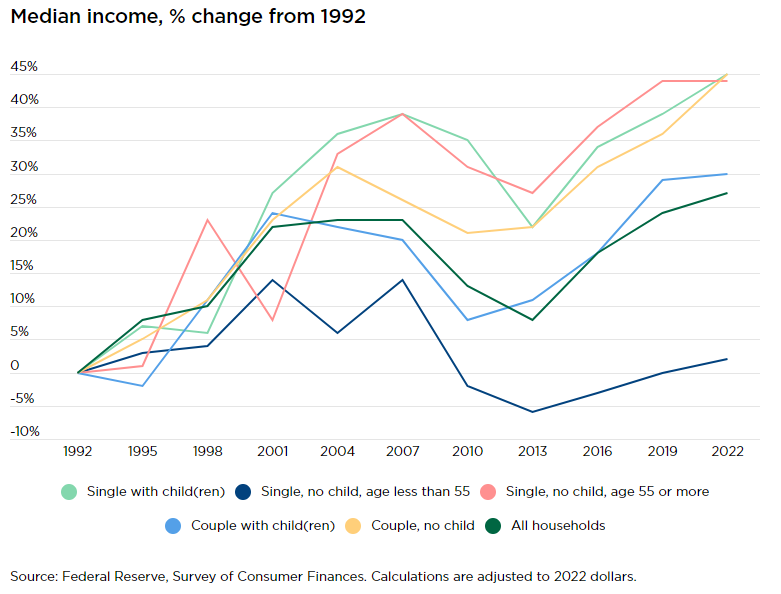

Over the past 30 years, the median annual income of single-parent households has grown just over 45%, after adjusting for inflation, to $43,000, slightly faster than any other household type. Across all households, typical incomes grew about 27% during that period.

Note: The Survey of Consumer Finances defines single-parent households as those with children but not married or living with a partner.

A higher real income means a higher standard of living — your money can go further toward paying for the things you need. And my personal experience as a child and a parent aligns with this data — later in my daughter’s childhood, I was better able to afford things my mother would have considered luxuries when I was young.

I want to make it very clear that it’s little more than a neat coincidence that my personal life reflects the Federal Reserve data. Much is hidden in national aggregates, and many people have their own anecdotes that would run contrary to the data. In the case of “median income,” for example, we know that half of single-parent households earned less than $43,000 in 2022, and many likely earned much less. On the other hand, half earned more than that median amount. And though the national median grew during this 30-year period, some households surely experienced periods of declining income. Big aggregates allow us to examine broad trends, but they also sacrifice some details.

Net worth nearly triples; homes and retirement assets climb

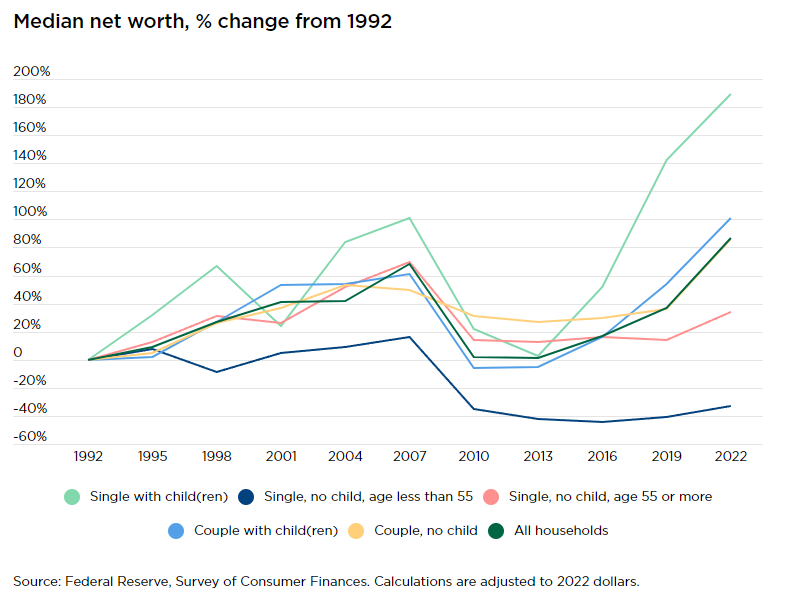

Your net worth is the amount of your assets (the things you own of value) minus your liabilities, or debts. And single-parent households saw significant increases in net worth from 1992 to 2022. While households overall saw inflation-adjusted net worth climb 87% during this period, those headed by a single parent rose 189%.

A higher net worth represents greater insulation from financial difficulties. When you have more savings, equity in a home or lower debt, for example, you’re better able to accommodate unexpected expenses and better able to plan for long-term financial goals.

At least some of this growth in net worth is due to the rise of homeownership among single parents. The percentage of single-parent households who own their primary residence grew from 43% in 1992 to 50% in 2022, an increase of 17%, and the most dramatic increase among all family types during the period.

I was raised in rentals; my mother hasn’t owned a house since she had to sell the family home after my parents’ divorce. However, I purchased my first home when my daughter was 7 years old, thanks in part to the more accommodating standards of an FHA mortgage, down payment assistance and when I bought — it was 2007, and home loans were being passed out like candy.

Another important asset, retirement accounts, are now held by 37% of single-parent households, compared with 24% in 1992. While a marked improvement, there is still room for growth here. Among all households, 54% have retirement accounts.

So what can account for these improvements? It’s likely a combination of factors, starting with a “catch-up” period. Moms make up 80% of the heads of single-parent households, according to the U.S. Census, and women were afforded the right to apply for credit and loans such as mortgages only in 1974. The full implications of this change could certainly take decades to work their way into household personal finances and the economy at large. Further, the share of single mothers who work and the share of women going to college has increased over the past several decades, contributing to increased earning power. And finally, while a 2022 Pew Research Center survey found that the stigma of single motherhood is on the rise again, it’s likely still at a better place than 30 or 50 years ago, when legal protections against discrimination were lacking.

Where single-parent households can still gain ground

The share of single-parent households that save money actually fell over the 30-year period examined, from 45% to 41%. In fact, it fell across most household types during this period, though it fell the furthest for single parents. Without savings, you’re more likely to depend on debt when emergency expenses arise and less likely to be able to keep up with monthly bills.

Single-parent households are also the most common household type to revolve credit card debt, or carry it from one month to the next. More than half (52%) of these households carry a balance on their card from month to month, compared with 44% of all households, according to the data. Further, single-parent households saw the greatest change in this metric among all household types during the two-year period capturing the COVID-19 recession — from 2019 to 2022, that share rose 15%.

Carrying credit card debt increases monthly payment obligations, and household payment-to-income ratios reflect this. In any given month, roughly 11% of single-parent households have monthly debt payments exceeding 40% of their monthly income. This 40% threshold is considered a measure of financial vulnerability, and a greater share of single-parent households find themselves on the wrong side of this line than any other household type. Further, while the share of households over this 40% mark has decreased in the last 30 years, it’s fallen the least in single-parent homes.

Keys to continued improvements

Overall, typical household finances have improved over the last 30 years, and by some measures they’ve improved most dramatically for single-parent households. But going it alone as a parent, whether by choice or by chance, still presents some greater financial challenges. Namely, households like mine often lack the additional safety valves afforded households with two potential earners, making them more vulnerable and more likely to have to turn to debt in periods of financial stress.

For me, a single parent raised by a single parent, money decisions were always about caution and resourcefulness, being careful and conscientious about every dime spent and being a scrappy problem-solver when money was too tight to cover all of the expenses. Honestly, I was resentful of this as a child. But I was grateful for the foundation when I became a parent. Early in my daughter’s life, these lessons were crucial for keeping the lights on, quite literally. And now that I’m financially secure, these lessons still underpin how I think about money and how I talk about it in my work.

The average finances of single-parent households have improved over the years, but individual household finances can hit setbacks along the long-term climb. The path to financial security is rarely linear. Incrementally building an emergency fund, using debt strategically and knowing where to turn when things get tough can make it easier to rebound and get back on an upward track.